GANS - A Deep Dive Into Automatic Image Colorization

Last month I decided to teach an AI to colorize black and white photos.

Though, I do have experience training deep neural nets, this was my first time messing with image colorization. I also decided that for my first attempt, I would avoid researching existing architectures ahead of time to see how far I could get with just my existing knowledge of deep learning.

My first attempts at this failed, but understanding why they failed taught me something important about how deep learning actually works.

The First Attempt ¶

My initial plan was pretty simple: build a neural network that takes grayscale pixels as input and predicts RGB color values as output. This is a standard regression problem.

I downloaded about 10,000 images from ImageNet, resized and converted each one to grayscale to create input data, and kept the original color versions as the target outputs the network should learn to produce.

The architecture I built was a simple convolutional neural network with just a few layers, nothing fancy or particularly clever about it:

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

class SimpleColorizer(nn.Module):

def __init__(self):

super().__init__()

self.conv1 = nn.Conv2d(1, 64, kernel_size=3, padding=1)

self.conv2 = nn.Conv2d(64, 128, kernel_size=3, padding=1)

self.conv3 = nn.Conv2d(128, 256, kernel_size=3, padding=1)

self.conv4 = nn.Conv2d(256, 128, kernel_size=3, padding=1)

self.conv5 = nn.Conv2d(128, 3, kernel_size=3, padding=1)

def forward(self, x):

x = torch.relu(self.conv1(x))

x = torch.relu(self.conv2(x))

x = torch.relu(self.conv3(x))

x = torch.relu(self.conv4(x))

x = torch.sigmoid(self.conv5(x))

return xI used Mean Squared Error (MSE) as the loss function, which measures how far off each predicted color value is from the actual color in the original image:

After some tinkering, I ran it training for a few hours and when I checked the results once it was finished, it was surprisingly bad. The network had clearly learned something, since it wasn’t producing random noise, but every image had this muddy, sepia-like brownish quality to it.

Understanding the Problem ¶

My first instinct was that maybe the network needed more parameters to be able to learn. I spent the next few hours trying every standard fix: various learning rates, deeper architectures with more convolutional layers, data augmentation techniques, batch normalization between layers, and dropout for regularization.

The results improved marginally but never became actually good. The fundamental problem of muddy, desaturated colors persisted no matter what I tried.

After a while of failed attempts, I stopped to think about what was actually happening from the network’s perspective. Consider a grayscale photograph of a car: there’s no way to determine from the gray values alone what color that car actually is. A red car and a blue car photographed under the same lighting might have identical grayscale values. The information simply isn’t there to be 100% accurate in a guess all the time.

Now consider how MSE loss works during training. When the network sees a grayscale car and predicts red, it gets a perfect score if the car was actually red, but a large penalty if it was actually blue. Over thousands of training examples, the network sees cars of every color: red ones, blue ones, white ones, black ones, silver ones. What prediction strategy minimizes the average error across all these different colored cars?

The answer is to predict the average color of all cars. If the network outputs a brownish-gray color (roughly the average of all car colors it has seen), it’s never exactly right but also never catastrophically wrong. The error is moderate for every example. In contrast, if it makes bold predictions like pure red or deep blue, it sometimes scores perfectly but sometimes fails completely, resulting in a higher average error, preventing it from making bold color decisions especially early on in training.

This is exactly what my network learned to do. For every pixel where multiple colors were plausible (which is most pixels), it hedged its bets and predicted something close to the statistical mean of all possibilities, resulting in muddy, desaturated, sepia-like colors.

Why Standard Loss Functions Fail Here ¶

This failure reveals something fundamental about regression with standard loss functions. MSE and similar losses assume there’s a single correct answer (or direction) that the network should learn to predict. When there are actually multiple plausible answers (like different valid colors for the same grayscale input), these loss functions push the network toward predicting the average of all possibilities rather than committing to any single plausible option.

The network was doing exactly what I trained it to do: minimizing pixel-level error averaged across the dataset. The problem was that minimizing average error doesn’t align with what we actually want from a colorization system. We don’t want the mathematical average of all possible colorizations, but one specific, plausible colorization that looks like a real photograph.

So how can we fix this? How can we get a neural network to commit to specific color choices rather than hedging with averages?

Generative Adversarial Networks ¶

After reading through research papers on image colorization, I found that most successful approaches use variations of Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) to solve exactly this problem. The GAN framework completely changes how we train the network by introducing a second network that acts as a critic.

Instead of one network trying to minimize error against ground truth, you have two networks in competition. The Generator network tries to produce convincing colored images from the grayscale images, while the Discriminator network tries to distinguish between real color photos and the Generator’s fakes. This setup is often explained with an analogy: the Generator is like an art forger trying to create convincing colored images, while the Discriminator is an art expert trying to spot forgeries.

The key insight is that the Generator’s goal is no longer to minimize pixel-level error. Its new goal is simply to fool the Discriminator into thinking its output is real. This changes the incentives completely. If the Generator produces muddy, averaged colors, the Discriminator will immediately recognize these as fake because real photographs don’t look like that. To have any chance of fooling the Discriminator, the Generator must produce vibrant, committed color choices that resemble what appears in actual photographs. At the same time, the Discriminator becomes better at distinguishing real color images from the fake colorized ones from the Generator, forcing the Generator to improve further, in a positive loop improving both networks.

Here’s how I implemented the two networks in PyTorch:

class Generator(nn.Module):

def __init__(self):

super().__init__()

# Encoder (downsampling)

self.e1 = nn.Conv2d(1, 64, 4, stride=2, padding=1)

self.e2 = self.conv_block(64, 128)

self.e3 = self.conv_block(128, 256)

self.e4 = self.conv_block(256, 512)

self.e5 = self.conv_block(512, 512)

# Decoder (upsampling) with skip connections

self.d1 = self.upconv_block(512, 512)

self.d2 = self.upconv_block(1024, 256) # 512 + 512 from skip

self.d3 = self.upconv_block(512, 128) # 256 + 256 from skip

self.d4 = self.upconv_block(256, 64) # 128 + 128 from skip

self.d5 = nn.ConvTranspose2d(128, 3, 4, stride=2, padding=1)

def conv_block(self, in_c, out_c):

return nn.Sequential(

nn.Conv2d(in_c, out_c, 4, stride=2, padding=1),

nn.BatchNorm2d(out_c),

nn.LeakyReLU(0.2)

)

def upconv_block(self, in_c, out_c):

return nn.Sequential(

nn.ConvTranspose2d(in_c, out_c, 4, stride=2, padding=1),

nn.BatchNorm2d(out_c),

nn.ReLU()

)

def forward(self, x):

# Encode with storing intermediates for skip connections

e1 = self.e1(x)

e2 = self.e2(e1)

e3 = self.e3(e2)

e4 = self.e4(e3)

e5 = self.e5(e4)

# Decode with skip connections

d1 = self.d1(e5)

d1 = torch.cat([d1, e4], 1) # Concatenate skip connection

d2 = self.d2(d1)

d2 = torch.cat([d2, e3], 1)

d3 = self.d3(d2)

d3 = torch.cat([d3, e2], 1)

d4 = self.d4(d3)

d4 = torch.cat([d4, e1], 1)

out = torch.tanh(self.d5(d4))

return out

class Discriminator(nn.Module):

def __init__(self):

super().__init__()

# PatchGAN discriminator

self.model = nn.Sequential(

nn.Conv2d(4, 64, 4, stride=2, padding=1), # 1 gray + 3 color channels

nn.LeakyReLU(0.2),

nn.Conv2d(64, 128, 4, stride=2, padding=1),

nn.BatchNorm2d(128),

nn.LeakyReLU(0.2),

nn.Conv2d(128, 256, 4, stride=2, padding=1),

nn.BatchNorm2d(256),

nn.LeakyReLU(0.2),

nn.Conv2d(256, 512, 4, stride=1, padding=1),

nn.BatchNorm2d(512),

nn.LeakyReLU(0.2),

nn.Conv2d(512, 1, 4, stride=1, padding=1)

)

def forward(self, gray, color):

x = torch.cat([gray, color], 1)

return self.model(x)The Generator uses a U-Net architecture, which is shaped like the letter U when you visualize it. The left side of the U progressively compresses the image down to extract high-level features, the bottom processes these features, and the right side reconstructs the full resolution image. The crucial innovation is the skip connections that bridge across the U, carrying fine details like edges and textures directly from the input to the output layers. Without these connections, small details would get lost in the compression and decompression process.

The Discriminator uses a PatchGAN approach, which means instead of classifying the entire image as real or fake with a single output, it divides the image into overlapping patches and classifies each patch independently. This forces the Generator to produce realistic textures and details everywhere in the image, not just get the overall composition plausible.

Training the Adversarial Networks ¶

Training a GAN is fundamentally different from training a standard neural network. Instead of steadily minimizing a loss function, you’re managing a delicate balance between two competing networks that are trying to outsmart each other.

The training alternates between two phases. First, you train the Discriminator by showing it a batch of real color photos (labeled as real) and a batch of the Generator’s outputs (labeled as fake), then update its weights to better distinguish between them. Second, you train the Generator by having it create colorizations and updating its weights to better fool the Discriminator. The interesting part is that when training the Generator, you never tell it what colors the image should actually have; you only tell it whether it successfully fooled the Discriminator.

My first attempt at GAN training failed catastrophically. The Discriminator quickly learned to spot every single output from the Generator as fake, which makes sense because initially the Generator was producing near-random colors. Once the Discriminator became too confident, it would simply label everything from the Generator as fake without providing useful gradients for improvement. This is like trying to learn to paint when your only feedback is someone constantly saying “fake” without any indication of what specifically looks wrong.

The solution was to pre-train the Generator using standard MSE loss for about five epochs before introducing adversarial training. Yes, this produces the muddy colors I spent so much time complaining about, but it gives the Generator a reasonable starting point. When the adversarial training begins, the Generator is already producing colorizations that are at least structurally coherent (somewhat), even if the colors are boring. This makes it much easier for the two networks to find a productive training dynamic.

Another thing to note is mixing a small amount of L1 loss (absolute pixel difference) with the adversarial loss when training the Generator. The combined loss looks like this:

Discriminator Loss ¶

The discriminator tries to tell real pairs from fake ones:

First term: loss on real (grayscale, color) pairs

Second term: loss on fake (grayscale, generated color) pairs

Generator Loss ¶

The generator tries to fool the discriminator while staying close to ground truth:

First term: adversarial loss (fool the discriminator)

Second term: L1 distance to ground truth (pixel-wise accuracy)

Variables ¶

-

-

-

-

-

The key insight is that the discriminator learns what realistic colors look like irrespective of its accuracy to the specific image, while the L1 loss term prevents the generator from ignoring the actual colors entirely.

Or in code form:

def train_gan_step(generator, discriminator, gray_images, real_colors):

# Training configuration

lambda_l1 = 100 # Weight for L1 loss

# Generate fake colors

fake_colors = generator(gray_images)

# Train Discriminator

pred_real = discriminator(gray_images, real_colors)

pred_fake = discriminator(gray_images, fake_colors.detach())

d_loss_real = F.binary_cross_entropy_with_logits(

pred_real, torch.ones_like(pred_real)

)

d_loss_fake = F.binary_cross_entropy_with_logits(

pred_fake, torch.zeros_like(pred_fake)

)

d_loss = (d_loss_real + d_loss_fake) * 0.5

# Train Generator

pred_fake = discriminator(gray_images, fake_colors)

g_loss_gan = F.binary_cross_entropy_with_logits(

pred_fake, torch.ones_like(pred_fake)

)

g_loss_l1 = F.l1_loss(fake_colors, real_colors)

g_loss = g_loss_gan + lambda_l1 * g_loss_l1

return d_loss, g_lossThe L1 loss serves as an anchor that keeps the Generator grounded. Without it, the Generator might produce beautiful, realistic colors that have nothing to do with the input image, like coloring a photo of a dog to look like a sunset. The L1 component ensures the output remains structurally aligned with the input while the adversarial loss pushes it toward realistic colors.

Results and Observations ¶

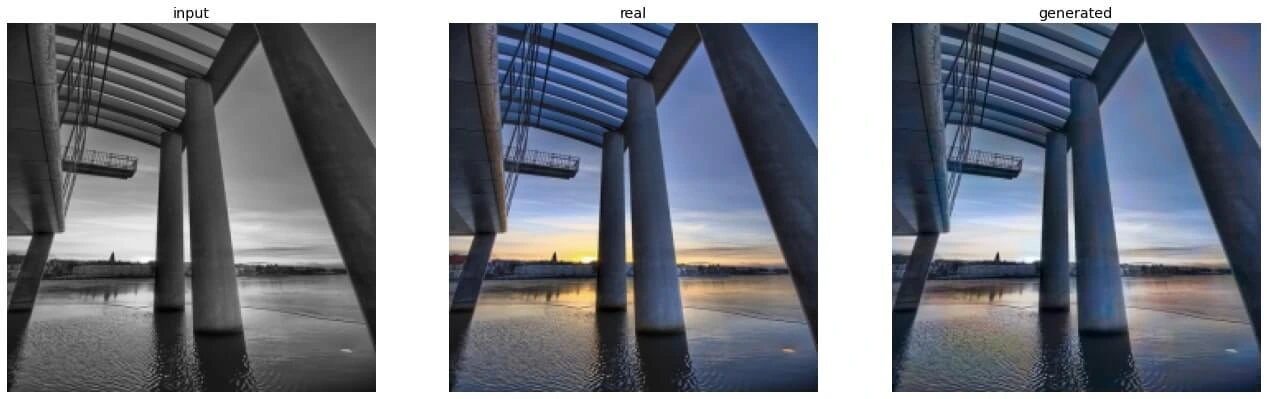

After training, the results were dramatically different from my original attempt. Grass came out properly green, skies were blue, and the network even learned subtle patterns like making shadows slightly blue tinted and highlights slightly warm.

More impressively, the network learned to make coherent decisions across objects. When it decided a car was red, the entire car would be red, not a patchwork of different shades. It understood that objects typically have consistent coloring and that certain color combinations commonly appear together in nature.

The results were not perfect, and sometimes the network made bizarre color choices, but overall the colorizations were much more vibrant and plausible.

LAB Color Space ¶

One final improvement came from switching the color representation from RGB to LAB color space. In LAB, the L channel represents lightness (essentially the grayscale image), while the A and B channels represent color along green-red and blue-yellow axes respectively. This separation means the network only needs to predict the two color channels, since we already have the lightness information from the input grayscale image. This simplified the learning task and eliminated weird brightness artifacts where the network would accidentally make things lighter or darker while trying to add color.

Lessons Learned ¶

The main insight from this project is that your choice of loss function fundamentally determines what your network learns to do. MSE loss tells the network to minimize average error, which sounds reasonable but produces terrible results for problems with multiple valid answers. The network responds by averaging all possibilities together, which is mathematically optimal for that loss function but useless in practice.

GANs solve this by changing the objective from “minimize error” to “fool a critic,” which aligns much better with what we actually want: plausible, realistic outputs. The adversarial training forces the network to commit to specific choices rather than hedging with averages.

They succeed precisely because it optimizes for perceptual quality rather than mathematical error minimization. Of course, GANs come with their own challenges like training instability, mode collapse, and the need for careful balancing between Generator and Discriminator, but when done right in the right task, they work surprisingly well.